Interview | The Cyprus Weekly

Phedias Christodoulides interviewed us for The Cyprus Weekly. The full interview follows. (A shorter version of this interview appeared in The Cyprus Weekly on August 2nd, 2014)

Book ex Machina: An independent imprint based in Nicosia, specializing in publication of small runs and special editions of art and photography books. Its slogan: We love books, we make books.

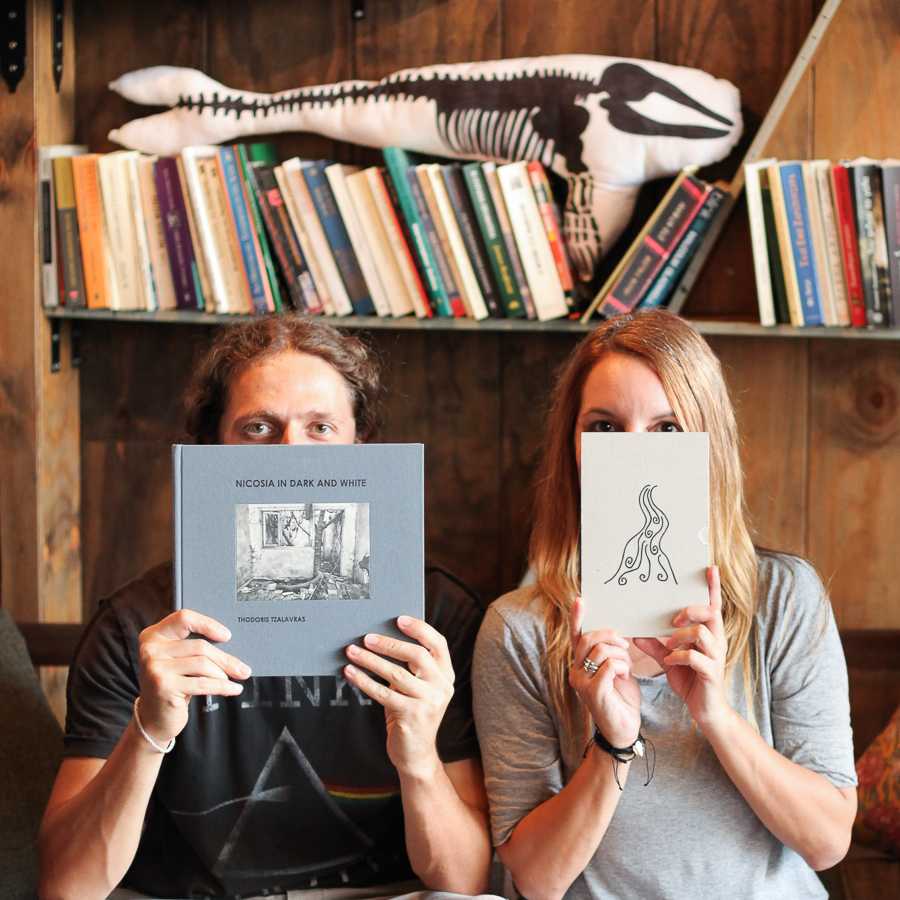

Ioanna and Thodoris: A pair of artists, a photographer and a writer, trying to leave their own artistic imprint on their surroundings and beyond. They are the couple behind Book ex Machina.

I met them downtown at café Prozak and we had a chat about their work, and art in general.

—Phedias Christodoulides

Thodoris, “Nicosia in Dark and White” was your first publication. What was the inspiration behind it? Your artistic aim for the project?

The project itself was something that I felt I had to do after coming here, in Nicosia, for the first time, in 2002 for my military service. Even though I am half-Cypriot, I did not have a relationship with Nicosia. So 2002 was my first time here and I felt that I had stumbled upon a surrealistic reality, walking down roads that led to barricades, hearing the hodja…It was a creepy and a completely out of the norm experience for me. I found it to be very powerful, but I could not explain it in words. Therefore, I thought that I would come back sometime and make a picture presentation of how I felt about this reality.

The book reads: “All pictures were captured with the existing light entering those places, with a medium format camera on tripod and long exposures.” Why did you specifically choose this photography format?

My approach to the subject is a combination of documentary photography and art photography; I manipulated somewhat the tonalities of the pictures in the dark room, but I did not want to manipulate the subject itself. I wanted to light the pictures with whatever light was actually present, and therefore I had to go to some of the rooms at different times of the day for the light to be as I wanted it to be—I wanted these places to be as they really are, while I wanted the emotional content to be controlled somewhat.

Why not shoot in color?

I shot the first few places both in black-and-white and in color, and I found that the color pictures distracted the project from what I wanted to say. Some of the places had very colorful walls and created a rather playful atmosphere that was not what I had in mind. This project had to do with me, expressing my point of view and my own feelings—I do not present reality but my reality and consequently when I compared the black-and-white pictures with the color ones it became completely clear that I had to shoot in black-and-white.

I believe that in some ways “dead” places are actually more alive and more interesting than “living” places, as your pictures show, especially in contrast with the wider, living Nicosia as we have come to experience it. Wouldn’t you agree?

I’m not sure. Any successful picture to some extent surpasses real life because it captures something interesting, while a moment by moment living of life is not always interesting. The pictures here are so successful precisely because they capture something at its most interesting. But interesting pictures can be made out of everything.

There are a number of hazy, ill-defined human figures in some of the pictures. Where they staged or passersby? Why are they there? Also, there is an apparently new portable stereo.

The three or four pictures that feature people in them are of places that are actually next to the main street, which is in use by people. Nothing is staged in any of the pictures. It happened, but I had to wait for it.

Why was it so important to include them?

I knew the aesthetic outcome of shooting moving people with long speeds, and I thought it would be interesting to try and capture the world actually existing outside these rooms, a world still moving, breathing and living, but without defining it…it is mostly shadows. Not everything is clear at the moment of creation—I just had the feeling that this might be interesting in this setup.

Regarding the stereo, some of the places are still visited by people and have some of their things in them—I had to revisit some of the places because of the light and I found that some of the things had been moved during the interval. The stereo, for instance, had been moved to another part of the room. As I wanted to show the rooms as they really are, I showed that some of them are still used by young people. It is a hint of something else than the project’s main theme.

One picture that particularly caught my attention is the one with the pegs. The gradual decomposition of the wall makes the photograph resemble a surrealist painting. Nature as an artist is at work on its own, and you as a photographer are there to capture it. How do you view the role of the photographer? Are you there to reproduce reality, give increased attention to reality, reveal a different reality through the lens? In other words, do you consider yourself a mediator or an agent?

This is a very complicated topic—I am conflicted about it. There are photographers who create worlds out of nothing by staging things, but that is not my approach. I am a facilitator of reality to some extent, but the final outcome is affected greatly by the way I choose to approach this reality. That approach in itself is the grey line between being a facilitator, seeing something and capturing it, and a creator, in the sense of creating something that nobody else would have seen existing but you. Even though I did not create the subjects of my pictures, I chose how to see them. The process of arriving to the way you see a thing is a creative process in its own right, because the same thing may mean nothing to another photographer and he will not choose to shoot it. Sometimes I am just a facilitator of something I just saw, but other times I feel that I have created something out of almost nothing.

Ioanna, you wrote a short story from a refugee’s perspective that follows the introduction to “Nicosia in Dark and White”. Why did you choose the theme of the refugees to go along this book?

After Thodoris finished his project he asked me to write something about it. I write fiction and I always try to put myself in other people’s experiences as I find this more interesting than writing about your own self, and I wanted to write a story that would fit with the book and would give the reader another aspect of the subject matter. So I decided to tell a story from an imaginary grandfather’s perspective, from the perspective of somebody that was an adult during the invasion. The cynicism and the jokes come from me. But overall I wanted it to be real, and thus it is pessimistic; there is this situation for 40 years and to be optimistic about it you either need to be very young or very crazy.

THODORIS: Regarding the political dimension of the project, I did not want it to be a political project because the political situation is very complicated and ambiguous.

I feel that you let people make their own conclusions.

Yes, that is why there are no texts along with the pictures. Some people asked me why I did not say where this place is, or the name of its owner, but I see these pictures as representations of a whole. I wanted the sum of the pictures to give a general idea of how I feel about this whole subject—the work thus functions rather like a metaphor; despite its documentary elements it is ultimately an art project. I wanted to remove any type of wider political opinion because I did not want anyone to add or subtract anything from what I wanted to express.

Ioanna, what motivated and inspired you to become a short story writer? What do you hope to achieve via your work/profession in general?

I have always wanted to be a writer. I started reading really early and I started reading a lot. So, I always thought that when I grow up I would write a book too. Then I got sidetracked, but writing remained the only thing I felt passionate about, so I returned to it. I am not really sure why I specifically write short stories, it just happened that way. I really like reading them and I really like writing them—I love writing fiction. I have a really good time when I am writing a story, I am fascinated by how it will turn out. And I am currently working on a novel too, for the first time.

I took a look at your “Matchbook Stories”: highly original format. How did you think of it, and what in your opinion makes it special?

As an object it’s really cool and people really like it—it’s really small, really cute. The first issue was handmade as well. I am not sure how it came about, I was just playing with matchbooks and the idea came. I like the idea that something so short and so concise can be so good at the same time. We are doing the second issue right now, it is going to be [printed in] about 2,000 pieces and will include work from three wonderful writers. Also, sure there are digital books now and the internet, but we still like the actual object and I was searching for ways to make literature into anything, make it more playful.

The object itself has a role to play; it forms part of the literary work.

Yeah, it adds to it, and even a person that is not interested in literature may pick it up because it is beautiful.

THODORIS: Part of the Book ex Machina project is about the object itself. The content is one thing, but the object, the way you present it, is a different thing. We try to find a way to make it as attractive and beautiful as an object in its own right as possible. First comes the content, but there follows an interplay between how to present it and the content, before we finalize how it will actually look.

The medium is part of the message.

IOANNA: Yes, because this has something to do with how the publishing world in general is evolving right now.

THODORIS: There are many small, independent publishing houses that produce exquisite books, better books, as objects, than the ones big publishers were producing before.

I read some of your stories; they seem to be just about anything, but, trying to find a thread uniting them, I notice they are usually centered around solitary narrators and consist of existential and metaphysical ruminations coming out of fleeting images of everyday, ordinary events and impressions, sometimes more poetic like “Fall” and “Sketches for My Sweetheart the Drunk” and other times weird and humorous like “The Break-In” and “The Midnight Sun.” Do you find this is an accurate description?

This is a very nice description and I would like to use it.

There are many writers that believe that you cannot write about anything except yourself and that everything you write ultimately reflects on you, but you insist that you are writing from the perspective of other people.

Everything in a way is about you, but you are unconscious of it. Your mind is a puzzle made up of all these little pieces—things you have done, things you have seen, things you have thought about—but they are all jumbled together and you don’t know where everything came from. The worst thing for me is knowing how the story is going to end. It takes me forever to write it by going back to the beginning. If I don’t know how it will end it goes much faster, because I am interested and curious.

Which among your stories is your favorite and why?

This is a tough one—I don’t know. I have some that I really like for different reasons. There is one that I am proud of because it was 240 words and only two sentences. And there was one story I wrote that when I gave it to a friend to read he was so absorbed he forgot he was cooking and almost burnt his kitchen down!

Who are the writers, artists, people that influenced you the most in your work?

THODORIS: I know that people from the art and the academic worlds have a need to place artists in some historical and thematic context. However, I wanted to say that, especially as influences go, I, and I believe Ioanna [does] too, consider art as one thing. Subconsciously we are influenced by everything we love. I have directors that I love, authors that I love, actors that I love—all kinds of art beyond photography influence and interact consciously and unconsciously with my creative process.

IOANNA: I would definitely like to write stories that are as good as some of the songs I love.

And Thodoris, what about your upcoming project, “Spirits of the River”? What is it about and what do you want to achieve via it?

In 2012 we had the rainiest year in a hundred years here in Cyprus. Rain water in Cyprus is scarce and rivers dry up in the summer, so when in 2012 there was actual real rain I wanted to make something about the rivers coming back to life. And because at the time I was working with pinhole cameras I thought of combining the two. It was a very elusive idea and context, so I had to rush, and I managed to collect enough pictures for a small book and now we are trying to produce it.

IOANNA: We also gave the pictures to my friend Jing and she wrote some poems for the book, based on the pictures.

I see “Nicosia in Dark and White” has been an internationally-acclaimed project, being a finalist for Best Photography Book Award in Pictures of the Year International (POYi).

THODORIS: It was a huge award, third place for best photography book of the year internationally. We did not expect to win anything, the idea was just to be in the mix and be noticed by some of the top industry people that examine the submissions.

IOANNA: But in Cyprus there is not even an award for photography books.

Thodoris Tzalavras was born in Athens, Greece in 1978. His photographs have been exhibited at Thessaloniki Museum of Photography, Silver Eye Center for Photography, HOST gallery, and David Alan Harvey’s loft in New York as part of the Burn Gallery Show. He often shows his projects on his website tzalavras.com and at In Search of Lost Pictures, his blog.

Ioanna Mavrou is a writer from Nicosia, Cyprus. Her short stories have appeared in The Rumpus, The Drum, Litro, and elsewhere. Ioanna’s work can be found on her blog Travels and Daydreams.

Book ex Machina books can be found in bookshops and on their website bookexmachina.com

BOOK EX MACHINA: Much thanks to Phedias Christodoulides and The Cyprus Weekly for this interview.

Sign up for our newsletter to receive news and special offers